|

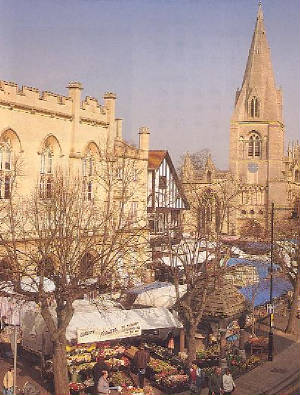

THE MARKET PLACE

The first Royal Charter to hold a market at Sleaford in the mid-1100s was almost certainly

a confirmation of something which had been going on here long before that time. Like the grant of an annual fair to be held

on St. Denys Day about 1140 and the start of building work on a new church around 1180, it was a sign of the new importance

which Sleaford was beginning to acquire in the century following the building of Sleaford Castle and the creation of a Borough

here by the Lords of the Manor, the Bishop of Lincoln.

Bishop Alexander The Magnificant of Blois (1123-1148) was

probably responsible for the present shape of the town. He set aside a proportion of the Manor of Sleaford and allowed its

inhabitants special privileges and freedom from the most irksome manorial dues.

Sleaford served as a convenient

centre for the produce of all the Bishops manors in the area, and the Borough encouraged the market to develop as an outlet

for this. In all probability the limit of the original medieval Borough was the River Slea in Southgate. North of this point

was the Borough, south of it the Soke or agricultural centre.

In 1978, archaeologists examining the northern and

eastern part of the Market Place uncovered signs that it was used for penning animals, probably during early markets held

here.

The earliest known market day (before 1202) was Sunday, so people coming to the town could combine their duty

to God with the pursuit of trade, all in one visit! After 1202, the market day moved to Thursdays, and by the 17th century

(as today) it was Mondays.

The area of the market place is much smaller now than it had been in medieval times.

It was sufficient to accommodate not only a large market but the regular fairs held each year, the chartered St. Denys Day

Fair in October and others on Plough Monday (an important Lincolnshire festival marking the end of the Christmas holiday),

Easter Monday and Whit Monday (which were really large markets) and the 12th August and 20th October (both cattle fairs).

Markets and fairs were valuable not only for the trade they brought but for the dues and tolls which the Lord of

the Manor could extract from them. In the Middle Ages, the Bishop sent his bailiff to collect the tolls on market days and

employed a man to go with him (presumably armed), to carry the locked toll-box between Sleaford Castle and the Market Place.

From at least the 17th century (and probably long before), corn could only be sold on market days after midday at which time

a bell known as the Market Bell or Butter Bell mounted in one of the bellcotes high on the west front of the church was rung:

a practice which continued well into last century. The bailiff then went round all the traders to gather the dues. Every trader

who did not live in Sleaford had to pay for pitching place or standing. Until Victorian times, large stalls were uncommon

and most people selling goods in the market travelled light and literally stood, with their waves in baskets around them.

The most favoured spots were under the eaves or penthouses of the private houses which surrounded the market place. The owners

of these were able to make a little profit out of the occasion by entering into deals with tradesmen who wanted to hawk regularly

there: the tradesmen paid a rent, and the owner of the house kept his pitch reserved, clean and in good repair.

By

the middle of the 19th century, the trade in corn had grown to such an extent that Sleaford like many towns in that period

invested in a purpose-built Corn Exchange which was one of the towns finest mid-Victorian buildings. Like most Victorian Corn

Exchange buildings, it was intended to serve a number of public functions.

On the western side of the corn Exchange

stood Sleafords largest and most select inn, the Bristol Arms. This has now disappeared, converted into the Bristol Arcade

shopping area. Its original name which it had sported since at least the 1530s was the Angel. Important public meetings such

as those leading to the enclosure of the towns open fields in 1794 often took place at the Angel.

The name change

early in the 19th century, bears witness to the considerable influence still wielded in the town at that time by the Earls

and Marquises of Bristol, who had been Lords of the Manor from the 17th century onwards. The Gothic style Bristol Memorial

Fountain installed in the Market Place in 1874 almost opposite the hotel, is a further example of this.

Although

Sleaford never became a chartered borough, with an independent corporation administering its own courts, it had been a focus

for royal justice (with gallows and a gaol) since at least the end of the Middle Ages. From Tudor times, Petty and Quarter

Sessions must also have been held in a court house here. In the early 17th century we know there was a Town Hall in the market

place, and a Town Loft (which probably indicates there was a covered trading area beneath). This remained the property of

the Lords of the Manor, who allowed the magistrate to use it for the purpose of holding the Sessions. It was pulled down in

about 1755 and replaced by a building in the Classical style, which had a walkway or arcade under the western side. This was

sketched before demolition in 1829 and can also be seen on the earliest town plan of Sleaford. By the end of the 18th century,

however, it was in a very dilapidated state and when, in 1826, Lord Bristol wanted to sell the Mitre public house, which stood

next door, the magistrates decided to buy both the pub and the old Town Hall and rebuild from scratch. The new Town Hall,

later known as the Sessions House, was completed in 1830.

Besides being a commercial and religious centre for the

town, the Market Place has been put to many less savoury uses in its long history. A pillory existed here in the Middle Ages,

and stocks and a whipping post were only taken down in the early 19th century. These all stood near to a market cross, the

last version of which (dated 1575 and opposite the north-west door of the church) was removed at around the same time. Wooden

statues of St. Mary and St. John, taken from the rood loft in the church were publicly burned in the Market Place during the

Reformation (21st October, 1559). In 1701, pernicious and antichristian Quaker books were given the same treatment by local

Justices of the Peace. Around the spot now occupied by the War Memorial stood a post and tether, used until about 1807 for

public bull baiting, which involved a contest between the tethered bull and a dog. Like the cock-fighting pit which used to

exist in a nearby inn yard, it is a reminder that violence and savagery were a common and everyday feature of 18th century

life.

|

| SLEAFORD MARKET AND ST. DENYS' CHURCH. |

|